This year the Royal Society of Portrait Painters awarded a new prize for the best small portrait. This prize attracted a cohort of diverse and intriguing submissions as well as an increased amount of attention from our visitors. Not only did they pause to spend time with this collection of small portraits, but they also bought many of the works that were for sale. The small works seemed to have a peculiar draw, but what is it that makes them so enticing?

History

Nicholas Hilliard

If we begin by looking at the more extreme end of small portraits we are led to a rich history of the miniature portrait. One of the most famous English limners, Nicholas Hilliard, revolutionised the artform from being a feature of a letterhead to a piece of art in its own right. Linda Bradley argues that the miniature portrait represented the “private” world through the “public” forms of ornament, convention, and rhetoric. It created a means by which you could show allegiance and loyalty to another within both political and romantic spaces: a miniature portrait of Elizabeth I, for example, acted as a piece of political propaganda. Even when the art was young, Elizabeth understood its power and she controlled her portraits carefully. By contrast, a miniature portrait of a lover would serve as a secret and intimate display of affection. This sets an interesting precedent for smaller portraits.

Of course, nowadays such antics might feel a little antiquated so we spoke to some of this year’s small portrait contributors about what the genre means to them and what they think it represents today.

Robbie Wraith ‘Studio Portrait’

Robbie Wraith

We began by talking to Robbie Wraith, who won the award for his self-portrait ‘Studio Portrait’ . He explained that smaller portraits are often more intimate, allowing people to commission beautiful pieces of art without feeling self conscious about the size of them on their walls. Wraith discussed the ways that our TV screens and technological devices have caused us to become somewhat visually desensitised and he suggested that the small portraits offer us an opportunity to retrain our eyes to appreciate images that are smaller than our screens; they allow us to look more “slowly and deeply”. He also noted that from an artist’s point of view, there is something quite special about having such a contained field of vision.

Elizabeth Meek MBE ‘Self Portrait’

Elizabeth Meek

Later, we spoke to Elizabeth Meek, also showing a small self-portrait, who was the former president of The Royal Society of Miniature Painters Sculptors and Gravers for many years. She explained that for her, the miniature speaks for itself without any necessary added context. Meek told us “the funny story of how [she] got into painting miniatures”. It all began when she “went into W H Smiths on a Friday to go and have a look at the sale books. There was a great big one on Miniatures for a fiver and so [she] bought it for that exact reason”. She explained that when she got home she “had a read and thought they were really beautiful.” Having already dedicated several years to painting, Meek was keen to give miniatures a go. She claims, “I sort of did my own thing though; I didn’t really know anything about miniatures or their history at this point, I was more interested in how artists were able to hone the skill of painting subjects to such a scale”. She notes, “there is a beauty in tiny things. Painting miniatures is very exacting and extremely complex. The smaller you go the harder it is.”

Meek, having now spent many years painting miniatures contends that whilst “miniatures have a long and rich history, in terms of where they fit in the modern day, the Royal Society of Miniatures is probably the best place to look”. She explains, “It is the largest society relating to miniatures in the world and it recently moved from just accepting portraits to accepting everything small such as landscapes.” She adds, “the society has a lot of collectors because miniature portraits hang together really well; they are a great way for people to begin buying original art.”

Interestingly, she also noted a somewhat competitive nature to the miniature: “I think people and other societies are definitely wary of miniatures more so than other artforms”. This is, perhaps, due to their novelty and irresistibility but, in general, she notes, “Most people are just really fascinated by them.” She explains that much of the forms’ ability to stay current comes from painters and society members who have found ways to develop miniatures in a more contemporary style, she specifically noted Davide Di Taranto here for his signature gold leaf miniatures.

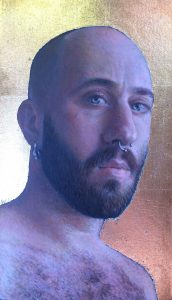

Davide De Taranto

Davide de Taranto ‘Eliran’

Following this, we spoke to Di Taranto who further outlined why small portraits remain so special. Taranto explained, “In my opinion, miniatures, in general, create a greater intimacy between the subject and their owner. I think they offer quite a nice contrast to the consumer society we live in.” When asking him about his exhibition piece ‘Eliran’, he told us that the portrait measures 120x70x2 mm, a size which he chose specifically because “painting with limited space helps [him] work in more detail.” He then explained some of his techniques that Meek so excitedly referred to: “As a general rule, I work by chromatic selection, painting in glazes and always letting the underlying material shine through. This allows me to control the colour layer by layer until I get vibrations of infinite invisible brush strokes. The portraits are also pocket-sized and can be very handy. In fact, they are the size of a business card or smaller.” Such an exquisite method would no doubt be lost on a larger painting.

When it comes to small portraits, it’s not just about size, it’s about connection, detail and marketability. The Royal Society of Portrait Painters hopes that this prize will have encouraged other to try this magnificent genre.

Find out more about commissioning a portrait.

Interviews and article by Ellie Lachs