Emmeline Downie takes a look at the works in this year’s annual exhibition that challenge and manipulate our traditional notions of time.

The last few months have been extraordinary. The global pandemic forced us to press pause and adapt to a “new normal”. We spent more time than ever before in the confines of our homes. Many faced a vastly reduced life. For some, time lost all meaning, the weekdays blurring into the weekends, each day lacking in distinguishing features. It is perhaps because of this that a bizarre, pertinent sense of timelessness is identifiable in this year’s exhibition. Many portraits transcend the boundaries of time altogether, from an ahistorical pregnancy via a writhing baby to the concise distillation of an entire industrious career.

Belinda Crozier, ‘Ruth, 37 Weeks’

Cultural critic Dr Wendy Steiner suggests that portraits usually convey identity as a “timeless essence rather than as a temporal unfolding” but this year many artists have flouted this definition. Instead, the temporal has been rendered in a state of flux, at times altogether indistinguishable, in utter defiance of being trapped on a canvas. One such example is Belinda Crozier’s painting ‘Ruth, 37 Weeks’ which manages to convey both a timeless essence and a temporal unfolding. Although it is a recent painting of her friend, Crozier establishes an unmistakable feeling of atemporality. Ruth’s hair, piled on top of her head and secured in knotted scarves, is most reminiscent of portraits by late eighteenth-century artist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. Furthermore, the painting is devoid of twenty-first-century trappings; the plain walls, wooden chair, and red robe only add to the agelessness of the image. The internal world of Crozier’s painting simultaneously straddles the centuries and conveys a very precise temporal unfolding – specifically the antepenultimate week of pregnancy.

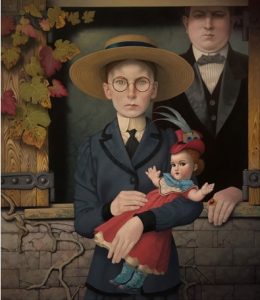

Tomas Clayton, ‘Worlds End Lane’

Tomas Clayton also looks to the historical in his imaginative work ‘Worlds End Lane’. The title, somewhat aptly for the current moment, refers to “a place of isolation”. Clayton rejects capturing the present in favour of creating a psychologically ambiguous portrait. He believes the present day is “far too quick for accurate interpretation”. The past offers more readability and a sense of quiet. His triple portrait is Edwardian in its content but modern in its rendering, complicating our relationship with its temporality. Clayton suggests the young girl has “lost the freedom of childhood”. We are left to reconcile her mature poise and stern expression with the uncanny doll she cradles in her arms. This curious, unsettling image denies us any comfort. Although we are invited to project our own mythic narrative onto the work, we may still struggle to make complete sense of the scene. Clayton subverts conventions of traditional portraiture and the obscured representations of age and time in the painting become fascinating collateral.

Miriam Escofet, ‘Childhood Consecration – Childhood Ontology Series’

Indeed, the depiction of children seems to intrinsically imbue works with a distinct sense of timelessness. Miriam Escofet puts this down to their mighty, boundless imaginative faculties. Her work, “Childhood Consecration – Childhood Ontology Series”, skillfully communicates the power of play. Where Clayton’s girl appears at odds with her doll, Escofet’s work shows the intense relationship children forge with toys. A marble takes on a sacred dimension, lying in the girl’s heart like a hagiographic reliquary. We are forced to acknowledge that this hyper-connectedness to seemingly menial objects is often lost when one enters adulthood. Escofet’s work can therefore be read as a reminder to re-engage with our naïve, awe-inspired, inventive selves. The plastic toys on the table are a mixture of the little girl’s own and some kitsch, vintage figurines Escofet picked up in charity shops. This results in neither a precise aesthetic nor an identifiable time frame. This portrait, therefore, is not simply a painting of a child but an homage to the very essence of childhood in all its fleeting playfulness.

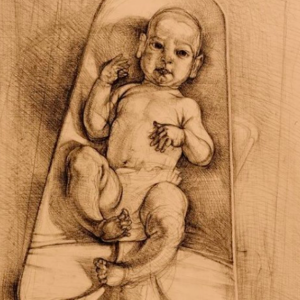

Toby Wiggins, ‘Ezra at 4 Months’

Children, although possessing enigmatic metaphysical qualities, also pose logistical complications. Toby Wiggins set about trying to capture his four-month-old son but, due to the constant movement of his sitter (or, rather, lie-er), ended up capturing something that never was. Wiggins adapted his usual method, drawing his son for five to ten minutes every day for a fortnight. His son would squirm, waving his arms and legs, and so Wiggins drew small sections at a time, never attempting to capture the whole body in one session. The resulting drawing is a composite of movements and gestures; a non-linear temporal unfolding. The faint traces of pencil marks show where Ezra once was, the history of his movements held within the image. Had Wiggins decided to draw from a photograph, the resulting image would have been unrealistically static. Instead, Wiggins’ method contains the animated essence of his son even if the moment captured in the final composition may never have quite existed.

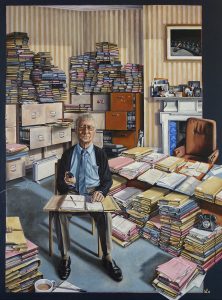

Nicholas De Lacy-Brown, ‘My Father, A Life of Work’

Lastly, not just a life but a lifetime is preserved on the canvas in Nicholas De Lacy-Brown’s painting ‘My Father, A Life of Work’. The portrait operates as a captivating time capsule, telling the story of De Lacy-Brown’s father, “encapsulated in the room where he has spent so much of his career as a local high street solicitor.” According to the artist, the room has looked this way since the 1980s. If we believe Aristotle’s definition of time – “the measure of change” – then this is a space in which time stands stubbornly still. De Lacy-Brown’s father refuses to succumb to modern methods of case management, instead relying on his dependable Dictaphone and paper filing system. Indeed, the files that surround him are architectural, perhaps even fortress-like, suggesting that his work is his castle; it is the physical evidence of the impressive career he has laboriously built. De Lacy-Brown is adamant that the quantity of files is not overstated and, if anything, he tidied them up in the composition. The all-encompassing nature of the work is therefore both metaphorical and literal. De Lacy-Brown’s addition of an abstract border around the painting further establishes the office as a self-contained world, untouched by time. His father sits sealed off from the modernity of the twenty-first century. And yet, the cord of the electric heater, the rotary dial telephone wire, and a heap of files and paper encroach into this liminal space, leaving us with the impression that this is a man who took his work home with him. The internal world is so full of personality that even were the figure to be absent, one gets the feeling this painting would still be a portrait.

This year’s selection deftly rejects the idea that contemporary portraiture should contain a single moment. Time is not just a by-product of these paintings but in varying ways an intrinsic tool, be it stylistic, compositional, or psychological. Surely, we are able to relate more to a sense of timelessness since becoming unmoored from our usual routines. Temporal ambiguity might be uncomfortable and disorientating at times but it is certainly enthralling.

Words by Emmeline Downie