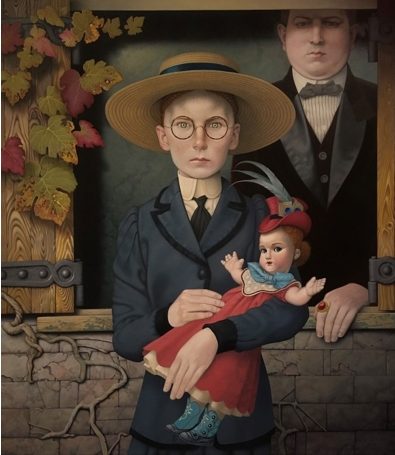

Upon initial viewing, Tomas Clayton’s “Worlds End Lane” is strikingly uncanny and enigmatic. It is not an innocuous scene. There is palpable tension and discomfort existing between the characters and the viewer. We are left forging imaginary relationships, trying to make sense of this odd triple portrait.

Despite the Edwardian dress, for Clayton this is an image that is full of personal relevance. All his paintings are vignettes of stories of his own making but this one in particular is closer to home. The image depicts his father and sister and their jarring, oppressive relationship.

“My father deserted my mother when I was a very small boy,” says Clayton. “The courts allowed him access to me and my sister, so every fortnight he would arrive in his little blue Austin A35. He loved his cars, he had a new one every year. My mother lived in penury. During these visits he used my sister’s love for him, his physical strength and his money to control and torment.”

Clayton’s stern father carries with him a feeling of omniscience. His penetrative gaze, despite being partially obscured by shadow, imbues the image with threat and defensiveness. It becomes a complicated image as we are left to reconcile this powerful, hypermasculne presence with the central protagonist, a trapped and vulnerable young girl. Clayton’s sister is pubescent but looks mature beyond her years. She has “lost the freedom of childhood”, now abruptly confronted by the social expectations that will dictate the rest of her life. The title “Worlds End Lane” echoes this sentiment; a road to nowhere, a “place of isolation” untouched by the rest of humanity.

This painting poses further threat to a pediophobic viewer. A fear of dolls is a common phobia and Clayton’s doll is certainly menacing. Her wide-eyed stare follows the viewer around the room; she is too animate, occupying the liminal space between toy and baby. Indeed, according to Clayton, the doll can be read as “a coquettish ceramic demon whose perfect complexion is beyond mere flesh”. The painting could be a vignette from a horror film, mere moments before some bloody incident occurs.

The past is a device that Clayton regularly employs in his work. He believes that the present is “far too quick for accurate interpretation.” He feels the trappings of the early twentieth-century lends a readability and quietness that a modern setting may lack. “It is still us”, he comments, “but without our iPhones”.

How do you feel about Tomas Clayton’s “Worlds End Lane”? Tells us on social media.

Words and interview by Emmeline Downie