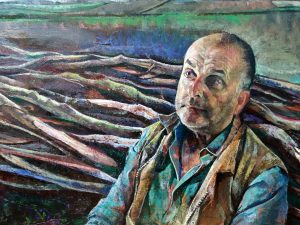

Image: Winter’s Work; Russell Woodham at rest while laying a hazel hedge in the Dorset Style

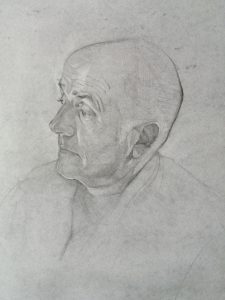

Toby Wiggins, ‘Winter’s Work; Russell Woodham at rest while laying a hazel hedge in the Dorset Style (Detail)’

The Painting

My interest in hedges and hedgelaying goes back to childhood growing up in the Dorset countryside surrounded by farm hedges, mostly, it has to be said, annually flailed within an inch of their lives. As a teenager and in my 20s I helped out on several local farms and helped to lay the odd hedge, done in the Dorset style, but I had no idea that there was any other way at that time.

Later still I began to visit and draw people who worked on the land in various capacities for a project for the BP Portrait Award at the National Portrait Gallery, London in 2007. This led to another exhibition at the Dorset County Museum in 2008. The interest remains and having noticed a new stretch of beautifully laid hedge nearby, I made enquiries and found ‘The Dorset Hedgelayer’ who was generous enough to allow me to visit him at work. It all started from there.

In my painting, Russell Woodham ‘The Dorset Hedgelayer’ is laying a hazel hedge grown on a low bank. It is laid in the ‘Dorset Style’ meaning flat to the ground with the ‘pleachers’ woven tightly ‘so as not to let a rabbit pass through’ as I was once told. The animals to be repelled are not rabbits, but sheep and so hedges laid in this style were and still are common right across Dorset and Devon on account of the medieval and later wool trade. Sheep remain a staple part of farming in this bit of England today.

I wanted to imbue the painting with a sense of the last light of a mid-winters day as the afternoon fades into darkness. The way in which colour drops out of the scene leaving a pewter sky and the occasional flash of silver along the keen edge of a billhook or on the fresh white cuts in the hazel pleachers, suddenly bright against the eye. These things I noticed when visiting Russell.

I wanted to embed Russell within the scene, not just place him in front of a landscape. To imbue the painting with a sense of his being part of this landscape. These hedges are his ‘umwelt’; his habitat as much as the livestock that they enclose or the creatures that live within them. I wanted the shapes in his work clothes to harmonise with the bowed and undulating hazel wands and the angular slices made by billhook or chainsaw to echo in the creases and folds. The colours too are analogous to those of the hedge so that he seems to sink into it; become part of it.

I wanted the viewer to feel closeness to the figure of Russell and his dog in the foreground, sharing the space with them, while being able to look beyond to a large expansive landscape.

When visiting Russell at work, I began to notice the repetitive rhythm of the action with billhook or chainsaw seemed to be about arcs through space. The pleachers are ‘plashed’ into the hedge from vertical through an arcing movement. Curves or arcs remained in my mind and affected the structure of the picture adding what seemed like appropriate shapes into the composition.

Optical accuracy in this painting is irrelevant to me. I never saw the whole scene as I present it. I caught glimpses. It is comprised of parts – a collage. Russell sat for me in my studio and I visited him at various jobs and sketched and watched. It tells a story, presenting a portrait of a man with the tools of his trade and hopefully a strong sense of place, at least from my particular perspective.

There are incongruities and deliberate manipulations of proportion and composition in order to better express the qualities that I could see and feel. It is an attempt to present an idea based on my understanding, as limited as that may be, and to get down what I witnessed – work which is physically tough and also solitary. These are far from negative attributes, but they are increasingly unusual in today’s world and require a certain resilience and character that few share.

Finally, it was important not to edit out the modern tools, the chainsaw and high viz chainsaw trousers and hard hat. Without these tools, the task would be extremely difficult as the present day job is often about bringing back large overgrown hedges after many decades of neglect. An axe and a billhook just wouldn’t cut it, if you pardon the pun.

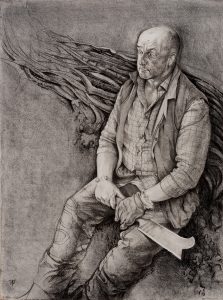

Toby Wiggins, ‘A Blackbird’s Tongue; Russell Woodham, The Dorset Hedgelayer’

Russell Woodham

Russell has been laying hedges in the Dorset, Devon and South of England styles for over 25 years and works every season from September to April. He is a member of the National Hedgelaying Society and many times competition winner and has lain over 30 miles of hedges single handed in his career so far. Russell has won multiple competitions and notably for the regrowth of his hedges.

Russell has worked at Highgrove, Sandringham and has conversed on the subject of hedgelaying with HRH King Charles who is also the patron of the National Hedgelaying Society (NHLS) of which Russell is a committee member.

He is currently involved in an advisory capacity with The Great Dorset Hedge, an initiative by Dorset Climate Action Network (Dorset CAN).

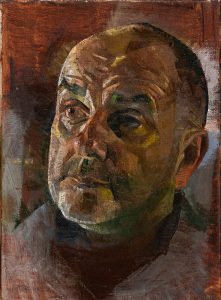

Toby Wiggins, ‘Study of Russell Woodham for ‘Winter’s Work’

Toby Wiggins, ‘Study of Laid Hedge, Midwinter’

Russell Woodham in conversation with Toby Wiggins 03 2023

“Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life” Mark Twain

What is the thing that you most love about hedgelaying?

Job satisfaction, most of the time. I’m rejuvenating old and neglected hedgerows, potentially saving them, bringing new life back to them, hopefully making a difference for both the hedgerow and the nature living in and around it. No matter what state or where the hedge is I will do my upmost to produce the best I can with it.

You can’t just rip out hedges, so my work will be there for tens of years, maybe even making it into hundreds of years.

Being outdoors, there’s no better office, as I say “some days the roof might leak” but it’s ever changing and no two hedges are the same or the surrounding countryside. I see and experience the changing of the seasons, which so many miss.

You have been doing this for many years now, do you feel a strong love/affinity for the landscape and the nature that you work in and with, chiefly the Dorset landscape? Would you say it’s in your blood?

I love the countryside I work in and being part of it. I’m Dorset born n’ breed and although I don’t read up on my county I still try to soak up any info I can. To me it’s brilliant to be able to do what I do and where I get to do it.

I get to see so many different views and landscapes that maybe the public don’t or won’t ever see, I’m happy to work anywhere, but yes, I do love Dorset. Such a mixture of landscapes I’d like to think it’s in my blood.

Any funny or strange or interesting things you’ve discovered in a hedge?

‘Hedge finds’, of course we would all like to see the glint of some treasure, but very regrettably rubbish is the main thing we find, sometimes “old” rubbish can be interesting, old bottles, jars preserved in the leaf mulch, shown the light of day again when I’m clearing ready for laying. Maybe even from the last hedger. On a few occasions we have found old bill hooks from past hedgers, put down until need, but fallen into the hedge, misplaced when clearing up and lost. A bit more modern, but I found some loppers just hanging in a tree, clearly been there many years; land owner saying the last person here was 15 yrs ago! Then of course there is the dreaded wire or bailer twine used by some for tying their hedge down. One of the worst things you can or could do.

What wildlife have you seen, anything memorable?

Whether it be working with hand tools or having a saw running, nature will always be close by. Many a time the second the saw stops you hear a rustling and you see a mouse or shrew moving down the hedge line. Just like gardening, it never takes long for a Robin or two to appear checking the ground you have disturbed. Often I’ve seen a fox just hugging the hedge line making their way back to the den, not so often, but also badgers just working their way along. Hundreds of deer over the years sometimes not bothered by you at all, others gone within seconds before you can get the camera or phone out. Being at one time a ferreter, one thing I have noticed is a great decline of rabbits.

I do like to see the birds of prey, many times their perched high up out the way I’m sure just watching to see of I disturb anything for them.

I’ve always worked outside. I first left school, went onto a YTS scheme and then, of all things, I went into Portland dockyard, working on boats, because a family friend knew someone with a vacancy and father was very keen on me having, like, a proper permanent job

Life takes a bit of a turn and I did a couple of years of building work and then I ended up out over Lulworth on the ranges as a range warden, so that certainly was outside country work.

I was doing a little grass cutting for someone on a weekend, beer money type thing, and that grew and grew so I started knocking me hours down at Lulworth and then took the plunge and went self employed. But, yeah, for a few years, grass cutting, hedge cutting, stuff like that. And then when the original River Cottage programmes came out, and I think he was just outside of Netherbury, one programme was about rejuvenating an overgrown hedgerow by laying it. The gentleman that was doing it, of all things, was a part time tutor at Kingston Maurwood College, Nigel Dowding. And after hearing that it can only be done in the winter, I thought, that looks a lot better than what I’m up to.

So I went on the course at Kingston Maurward agricultural college near Dorchester and I finally found something which I seemed to be reasonably good at, or maybe even very good at.

Nigel gave me my first job and I don’t know whether it was a ‘let’s see how keen he is’, but I always say I’ve not got the the best of memories, but that hedge was 261 metres of Hawthorne, probably about thigh size, and that was the first job I had. And I knew Nigel wasn’t too far away working and he just come on in at the end of the day and gave me a few pointers and said ‘no, that’s not too bad.’

You go to competitions, you meet people and word gets around and very early advertising cards in a newsagent window and away you go. And obviously, if you can do one job on one estate very well, the word soon gets around between landowners.

TW

Did he teach you a particular style to start with?

RW

Nigel taught us the Dorset style. The courses were up at Corscombe.

TW

I guess it was Dorset style, obviously, because it’s here and it’s mostly associated with sheep, isn’t it?

RW

A lot of Dorset is classed as lowland sheep farm country, certainly central to West Dorset, and then venturing into Devon. You get banks and your hedges are on top of the banks. So that first bit of stock proof is the bank and then the hedge being on top is the final piece. As you venture west, there’s no hard and fast line, you go across the border and it doesn’t have to be a Devon style or Somerset or Hampshire, as the case may be. Just round about Bournemouth/ Ringwood type thing, venturing in the New Forest, you start going over to ‘South of England’ style, predominantly, but there’s nothing to say that you can’t do South of England style in Devon, Cornwall or take it up to Scotland or take the Dorset style up to Scotland. If it’s relevant or if someone just really wants that then there’s no hard and fast rules.

TW

The styles evolved because of the type of stock?

RW

Keeping stock, but also the landscape, weather conditions, things like that have a part to play in the style. Things may have changed slightly now and then, but if you imagine your bank for Dorset/Devon hedge, would be anything from 18 inches to five foot, and then give or take two foot six inches, maybe three foot of hedge on top of the bank – So everything’s quite low and tight to prevent sheep from pushing through. But if you took a ‘South of England’ hedge or Midland or Derby type hedge and put that on top of a potentially five foot high bank, you’ve then got a total height of maybe nine foot! And it is almost like, dare I say, like a high fence; it’s just a big sail and a wind catcher and we do get strong winds across the county.

That’s how your styles have come about, just the differences in farming methods, livestock and terrain across the country. If you look at the UK as a whole, you’ve got Devon, Dorset, South of England and Somerset style all below that M4 corridor, then going on up through, you’ve got Midlands style, venturing off into Wales, there’s originally about 20 odd styles just in Wales alone. Going up through the centre of the country, Midland style, Derby, Staffordshire, Cheshire at the very top. Then you’re venturing up into Yorkshire. Yorkshire is probably the more different out of all of them. It’s almost like a post and rail and always reminds me of a horse racing track. It’s a very thin style for where they used to farm right up to both sides of the hedge.

Then after Yorkshire, you’re up into Lancashire Westmoreland style, which is, I always say, a third bigger than Somerset style, but sort of the same. Then if you go right on up to Northumberland and Argyle and Butte, you’re almost back to Dorset and Devon on top of a bank, windswept sort of places. So it is almost like a full circle around the length of the country regarding the styles.

In Dorset, everyone sort of knows or is familiar with the Dorset hedge, but the most recognised, if you just say ‘hedgelaying’ to somebody, is probably the Midland style. Just because it is done a lot more and covers a bigger area. The Midlands style is probably covering two thirds of the countryside. So it’s just more popular, more predominant.

It’s all cleaned one side, laid at 45 degrees with a stake combined in. Whereas the south of England, you have the brush both sides, but the Midland one is cleaned one side. That would have been your ploughed field for that season. All the brush sticking out the other side would have kept the livestock away from any new shoots from the planted crop. And yet again, just part of the rotational farming.

At the end of the day, there’s about 30 recognised styles. When you start adding them all up for the national championships, normally we have about ten classes.

TW

And what about the style where it’s hacked to death and tied with Bailer twine?

RW

That’s quite a different thing. Yeah, that’s the bane of any real hedgelayer’s life. I often think I’d like to cut the string, you go along and you see it all down the length of a hedge.

There’s just no need for it. Just genuinely, there is no need for it if they knew how to build well. The string is one thing and then you get the other ones over the years have used extremely thin wire and obviously when the chainsaw meets that, that is good fun. You should be able to use everything, either from the hedge or from your local coppice worker, no wire or twine.

TW

It’s quite interesting that you’ve mentioned your prizes for regrowth, which is key, really, isn’t it? It’s lovely to lay a hedge and make it look beautiful from the perspective of the structure and I know that you get judged on that to some degree, but if it isn’t going to grow back very well then there’s a problem.

RW

Now there are quite a few people that take part in competitions that have more emphasis on what it’s like the following year, and that they almost believe that the Regrowth Trophy is better than winning the competition, because that is the purpose, isn’t it? Depending on the draw and depending on what you’ve got in your bit of hedge, obviously some stuff could grow a bit quicker. So visually, they have had really good Regrowth. Just the other persons, as I say, is a bit slower growing and whatever. But no, it’s obviously all part and parcel if you can do really well at competition level. This is, of course, you can do really well and get a place that’s one thing and then come out as the regrowth winner the following year. Obviously, it’s real credit to what you’ve done and the way you’ve been able to maintain and revive the hedge, I guess.

Hazel obviously been used for hurdles and stuff like that for years, generations. You can tie a knot in the hazel, yeah that’s just so easy to work with. You get the short grain woods and long grains, basically. Some people hate working with thorn, funny enough, because it is prickly and horrible. But give or take, you can be quite brutal with blackthorn and that will give a very stock proof hedge. The likes of sycamore, maple, ash, maybe not so good, and also quite a brittle material to work with. Sometimes you need to be careful of the weather working and if it’s really cold. Some people say big hawthorns either the beginning of the season or the end of the season, when there’s either a bit of sap left in it or when sap’s coming through first. But if you work on that theory also in that you’re trying to squeeze loads of work in at the beginning or the end, where obviously you can only do so much.

TW

That is interesting that they would have a different tension or brittleness depending on the weather and the long or short grain of them.

RW

I’ve done stuff before where, even in the middle of winter the sap is coming out of the maple and you come in the next day and it’s frozen.

But, yeah, every season is different. Like this summer we’ve just had, no one can tell you what it’s going to be like. We have not had a summer like it since, I’m guessing ‘76, and the people that were still cutting then are very old and whether they can remember what the following winter was like? Some people were saying, this year, this winter just gone is going to be very brittle because there’s been hardly any moisture. And I sort of said, well, maybe they’d be very supple and quite flexible because they dragged every bit of moisture out the ground and stored it.

I found not really much difference at all. Alan said he always used to be able to sense the hazel had still a fair bit of sap or a bit less sap each season.

It also depends where the hedge is. If you’re tucked down in a valley out the way, the wind temperature doesn’t vary too much. It’s, shall we say, a nice, easy and standard hedge. You get up on top of a hill, we haven’t got any big hills in Dorset, really, nevertheless one, maybe two, degree different in windswept places and it can be sort of brittle and totally different to work with.

Another job I’d done over at Rampisham one year, I was still cutting and laying on well into spring, I finished a job on the 26 April. I was on the northern side. This is up on top of Rampisham. I was on the northern side of a pinewood, laying hazel and there wasn’t even any buds, and that’s on the 26 April. No sun was getting through that little bit of height, and it was just like laying in the middle of winter and everything was completely bare. I’d say that was 26 of April. So certainly no worries about bird nesting and stuff like that, because there wasn’t anything for them to have nested in. There was no cover, anything at all. But, yeah, the seasons vary once you’ve laid the hedge.

The nature of the hedge and how it fares and weathers and stuff like that, and obviously what the household/landowner/estate, what they want to do. Some will just leave them and say, we give you a call in 15 years. Others, I’ve gone back about four times now and he just wants it trimmed and tidied up and anything that’s raced away laid again.

If it’s been maintained, it could take 20, 25, 30 years for a thorn hedge to get back to its height again. Hazel, you could be going back in 10 to 15 years if it’s grown same sort of rate as when it’s been coppiced and with Hazel, you’re looking at 15 foot, maybe after seven, eight years. But yet again, that’s about just where it is, how it is, whether it be windswept or sheltered. In theory, though, it’ll always be there, there’d be signs or remnants of it always unless a farmer, landowner had managed to get permission for some reason to remove it or make a gateway bigger or something like that.

Sometimes you’ll look at a hedge and think, well, if it’s been there 200 years or more, why is it only two inch diameter stems? But obviously it’s the circle of life of having been laid and laid again. Well, either that or it’s died and fallen away and new shoots and suckers have come up.

I’ve looked at maps and gone, yeah, this is, I don’t know, 1700 or other, there’s evidence on a map that there’s a hedge there and in your head you’re thinking, well, it should be eight foot wide trunks and stuff like that, but no, it’s just rejuvenation. Suckers come up, bits die off. You’ll see a massive lump of ash laid horizontal, whether it be at ground level or anything up to about three foot high in a hedge. They can be waist size. It didn’t fall over in a storm, it is an old pleacher and some are so old that they’ve healed right over. You can no longer see where the cut was made.

There’s a good chance if there’s nothing underneath them that there was once a bank.

It might have been laid bank level in old Dorset, old Devon style and you would do what’s known as ‘casting up’. So you’d square up the side of your bank and then the soil from the base, you’d then chuck up on top of the hedge and just keep that sort of rotation going for years. Devon probably more so in that there they have what’s known as a ‘double comb’ hedge. Basically two hedges either side of the bank, and you cast the soil up into the middle.

And the middle of some of the double comb hedges, you could nigh on drive a quad bike down through. It’s almost like a footpath down through the middle, which suggests great age.

But over the years, over hundreds of years in some cases, the weather’s just eroded them, or the sheep have gone up and they tread a bit and tread a bit more and it just falls away and drops away. And next thing you’ve got a very gradual incline and what looks like a very high pleacher in a hedge because the banks dropped away underneath it. It’s fascinating to see those.

TW

How old is the practise of hedgelaying do you think?

RW

There are people quoting that they found remnants from Roman times. But then others will say, well, like African Nomads have used dead hedging for millenia. They go and find a load of brash each night to put round their animals, to just keep their herd of goats together, which is still a form of hedgelaying so perhaps it goes back to some form of this originally.

Live or Quick hedgelaying is predominantly a UK phenomenon. There are remnants of it in Holland of a different style, a very small bit to be found in Germany and likewise France. Ireland are, over the last 20 years, trying to bring it back. So it’s predominantly the top northwest of Europe, shall we say. But mainly in the UK.

I say there’s meant to be evidence from Roman times, remnants of and Julius Caesar wrote something about cut and pleat or pleach, anyhow, something about bending hedges at the end of the day. So through my own little bit of research on the Dorset side of Hedging, I found a date of 1646, basically an invoice for somebody who pleached a hedge, so I can’t think what else it could be. I’m pretty sure that he’s not getting a mix up with some religious connotations. But he pleached, I can’t remember the distance now. It was a real old school distance. But yeah, pleaching hedges was his invoice 1646. So the terminology has been around for quite a time.

TW

Now books on hedge Laying, I expect there are a few?

RW

Yeah, there is a fair few, and I don’t think there’s any definitive one.

I’m guessing like any book it’s all personal choice. I’m not a great book reader, but I’ve read them because of the great interest to me. I’ll say there’s a dozen in the circles of well known and popular books. But they will all have their good and bad points. Again, it’s all the individual’s personal good and bad points.

So I could go and take all what I think of the good points out of all the books and put them all together and someone could possibly still pick holes in what I then suggested. So then you end up with another book.

It’s no different to people being trained. I’ll train the way I was trained and try and hand down that tradition. Somebody else could be different to me and then you’ve got an argument ‘no, that’s not right, it should be done like this.’ So that’s where your differences can very easily come about.

TW

Tools wise, I think I have asked you this before. When I went to see Alan, I know it’s entirely different, but he had about five hooks, little ones and bigger ones. And there’s just that traditional shape. Is it just your preference to have the unusual double edged one or is that a particular style of hook?

RW

The style is a Yorkshire bill hook.

The Dorset one won’t have that flat blade, if you know what I mean. And it won’t have such a long handle. The Dorset one, dare I say it, will look like the ones Alan had with the shorter handle and only one sided blade still with the curve, the beak, whatever you want to call it, the nose. If you’re trying to work into the middle of a hazel stool, the curved side can catch on the growth that’s inside, what should we say, the cluster of stems that you’re working with. Whereas you turn it around and work with the other side, the flat side, it’s not going to get hooked up at all. And also with a slightly longer handle, you can use it as a mini axe.

It’s personal choice, bill hooks in general. I’ve had people on courses and I’ll say don’t just click on Ebay and go buy a bill hook. Give it that bit of time, go to car boots, stuff like that, or old emporium type places and pick a load up. It’s just the same as driving a car. You get in it and some people just get in and go, yeah, that would do it. And you get from A to B and others will go, well, that’s really nice to drive. And the same with the bill hook. You might not think it is, but it could be really heavy in the end. 2 hours in and your wrist is absolutely hanging off, where you pick up another one, not necessarily lighter, but just balanced better and it’s really nice. You get to the end of the day and you don’t realise that you’ve been swinging it all day. But now I’ve got about six or seven Yorkshire bill hooks and even then it could be sort of preference if it is a real busy hedge, if there’s loads of stuff in it I might use a slightly shorter handled one.

Over the years, every now and again, I get a sore or aching wrist or I’ve done something to it, I may have to turn to a lighter hook just for a few days. Wrist brace and a lighter hook.

Billhook, Axe and chainsaw that’s shall we say, the real essentials. And then obviously if you want to do the clearing out of bramble and such like, you need a sickle, slasher, hedge cutter and rake for tidying up and if you do in the south of England style, you need something to knock the stakes in with. But some old school will go, well, I’ve got an axe, just turn the axe around and use the other end. oh yeah and a decent set of gloves.

Yeah, potentially some people will work with two gloves, but depending on the nature of the hedge and that one glove, you can just always grab hold of the hedge. Wet leather on wet wood – if the conditions are like that, it’s not the best as they can slip. If you have a decent grip on it, it wouldn’t happen. But yeah, normally a glove on and the other shoved in the pocket or whatever if there is some big old thorn to handle. Obviously chainsaw-trousers and boots are a necessity for chainsaw. You see old school pictures, it’s just like a big old leather apron, others are just donkey jacket and previous to that smock coats, potato sacks tied like a skirt, but obviously just protection on the front and also real good old traditional English boot is what you need at the end of the day.

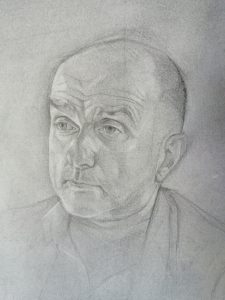

Toby Wiggins, ‘Preparatory sketch of Russell Woodham pencil on paper 01’

Toby Wiggins ‘Preparatory sketches of Russell Woodham’

Additional useful sources:

Clarkesons Farm season 2 Episode 6 – Russell features in Clarksons own hedgelaying competition and wins in the Dorset Class. ( aired 10th Feb 2023)

https://www.dorset-hedgelayer.co.uk/clarksons-farm-s2-episode-6/

https://www.instagram.com/dorset_hedgelayer/

https://www.facebook.com/Russellthehedgelayer/

https://www.dorset-hedgelayer.co.uk

MORE INFO ABOUT THE RP ANNUAL EXHIBITION 2023

Contact Annabel Elton – Head of Portrait Commissions: 0207 968 0963 | [email protected]